In a new book published by Phaidon, 200 everyday objects, right from the Bombay horn to Bata shoes, tell the story of Indian design

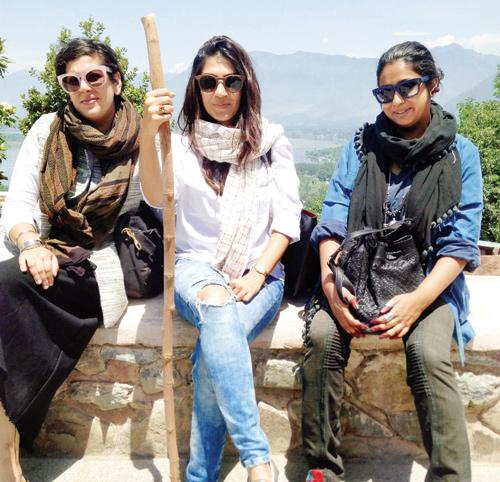

Swapnaa Tamhane, Prarthna Singh, Rashmi Varma

Inspired after a trip to India in 2011, Varma and Tamhane, who share a 15-year-long friendship, tinkered with the idea of presenting an exhibition of objects that strongly spoke of Indian design. They were sitting at a coffee shop in Toronto, where Tamhane is currently based. Eventually, the idea for a book, rather than an exhibition, was born. Varma, who now lives in New Delhi, says, “It’s not an exhaustive list; we started with 300 items and finalised 200. They include things that are very much in use today; in that sense, this is a very 2016 book.”

Shying away from stereotypes, the curators have paid attention to the evolution of objects too. Balancing a history of 5,000 years and the entry of machines, including the pressure cooker and mixer grinder, the book takes you through chapters titled after daily chores, like Sajna Savarna, Aana Jaana and Khaana Peena. It was hard to be pan-Indian with these titles, says Varma, and get a variety of Indian languages in, but they wanted to keep the tone accessible (while the price of the book at Rs 5,000 may not exactly spell ‘accessible’. But that’s luxury bookmakers Phaidon for you).

But is there something such as pan-Indian design? The book will tell you that there are 200 ways to answer that, or more, and Varma, shuddering slightly at the question, replies, “It boils down to certain techniques, materials and forms. But, it is also related to the economics of the country, influence of colonial powers, like the Mughals and the British, and a nationalist identity post-Independence. Sar ultimately, draws attention to the “designed object and not just aesthetics.”

Sar refrains from “hyper-colour and hyper-loud” images. “We didn’t want just a pretty picture of a lota,” quips Varma.

They chose to collaborate with Singh, whose work in fashion and reportage resonated with the needs of the curators. Travelling through North and West India, and gently persuading their way into new homes to explore certain objects, Singh says that she loaned “silence to the images”, letting the objects speak for themselves. “I chose simple khadi backgrounds or a brick wall that is recognisably Indian, without making it clichéd,” says Singh.

Eat Stack

Designed by Gunjan Gupta in 2009, with silver- and gold-plated brass, the Eat Stack was a contemporary interpretation of the traditional thali. The arrangement, reminiscent of temple gopurams and lamps, dismantles into a fully functional set-up to eat with. “Just when you think that an Indian object has been so well-designed that it can’t

be changed, like the thali, there comes a designer who introduces a new perspective.”

Meerut Barber Scissors

Meerut barber scissors came to India after England’s Industrial Revolution and are an apt example for recycling as they are made from scrap metal. Singh recalls that they had to scout New Delhi’s Chandni Chowk several times to get a shot of these, since the barbers, a 300-year-old community, were busy snipping away with these all the time. Sar reveals how these scissors have a Geographical Indicator (GI) tag, much like Darjeeling tea, “to prevent fraudulent replicas”.

Indian design, told through 200 objects, including this gola ice shaver, so ubiquitous on our roads, in Sar: the Essence of Indian Design, which will be available in leading bookstores and online portals. Pics/Phaidon And Prarthna Singh

Bajaj Chetak Scooter

Like the Maruti 800, this one took some hunting down. “We were looking for this scooter for some time, and then found it parked outside a tailor’s shop in Bandra. He was very proud of his vehicle and spoke of how it had never been serviced. We found a curtain of green foliage for background,” says Singh. The book recalls how the scooter was suitable for an entire family to travel on, until production ceased in 2009. ‘Hamara Bajaj’ as its advertisement labelled it, it was named after the stallion belonging to the Rajput warrior Maharana Singh Pratap. “The Bajaj Chetak is iconic. You cannot think of India without it,” says Varma.

Bata Tennis Shoes

“Like the Ambassador, which is not of Indian origin, these shoes were part of everyday material culture. These are functional, and at the same time, with their white colour, they are not,” says Varma. The book traces how these shoes, originally meant for physical training classes, are produced at the same factory in Batanagar, near Kolkata, since 1934. For the book, Singh shot these against red earth, and says, “Children began a new semester with these ‘PT shoes’. I wanted to get the white of the shoes against the red mud, reminiscent of a school ground.”

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

Subscribe today by clicking the link and stay updated with the latest news!" Click here!

_d.png)